Bottle Bill Resource Guide

What are “unclaimed deposits”?

In ten U.S. states,1 beverage distributors and retailers are required by law to collect small deposits (usually a nickel or dime) on certain packaged beverages.2 When consumers return these beverage containers to a retailer or redemption center, the deposits are returned to consumers. When consumers choose not to redeem their used beverage containers for the deposit value (either because they recycled them through curbside, drop-off, or public space recycling programs--or because they threw them in the trash or littered them), the deposit money is considered “unclaimed.” Other terms are “abandoned” and “unredeemed.” Depending on the state, unclaimed deposit funds are retained by beverage distributors, state agencies, or a combination of the two, and are used for various purposes described below.

Who keeps the unclaimed deposits?

Systems can be generally grouped into two categories: state-managed systems, and systems managed by the beverage industry.

1. State-managed systems

In California and Hawaii, state agencies manage and control the finances of the beverage container deposit system. In California, the agency is CalRecycle; in Hawaii, it is the Department of Health. These agencies collect deposits from distributors when the beverages are sold to retailers. The bottler or distributor pays the deposit directly into a state-managed fund and collects the deposit from the retailer. The retailer then collects the deposit from the consumer. Refunds are paid to the consumers out of the state-managed fund, which is also used to pay for program operation and administration. Hawaii's fund also receives one penny per container from beverage manufacturers to help fund the program. In both states, 100% of unclaimed deposit monies are used by the state agencies*to manage the system, educate the public, and promote markets for recycled material.

2. Beverage industry-managed systems

In the other eight U.S. deposit states, operations and finances are managed by the beverage industry, and unclaimed deposits are either retained by distributors or escheated by the state (in full or in part). Entities include:

2a) Distributors: In Iowa, beverage bottlers and distributors keep all unclaimed deposits.

2b) System operators: Oregon's bottle bill system is operated by the Oregon Beverage Recycling Cooperative (OBRC), which retains all unredeemed deposits to fund bottle collection. The OBRC reports that they also receive $9 million per year in funding from the beverage distributors and grocery retailers. 3

2c) State government: The deposit laws in Connecticut, Massachusetts, New York, Maine, Michigan, and Vermont allow partial or full escheats, whereby distributors and bottlers are required to turn over all or a portion of unclaimed deposits to the state. * The table below shows what proportion of unclaimed deposits escheat to each state, and how the funds are used:

*A note about escheats: Generally speaking, an "escheat" is simply the transfer of unclaimed property to the state or government. When state container deposit laws permit beverage distributors or retailers to keep some or all unclaimed deposits, those are not escheats. "Escheats" in the deposit-recycling world only refer to those unclaimed deposits that state governments keep by law.

How have escheated unclaimed deposits been used?

Escheated unclaimed deposits have been used for both environmental purposes and to supplement a state's general fund.

1. Connecticut

2. Maine: Maine’s escheat law was enacted in 1991. 7 Unlike the laws or provisions in Massachusetts and Michigan, Maine collected only 50% of the abandoned deposits, and the distributors and bottlers retained the other 50%. The revenue was used to fund the Maine Solid Waste Management Agency. Since the state received only half of all unclaimed deposits, and because Maine’s redemption rate for beverage containers was so high, the state chose to repeal the law in 1995, because the State was afraid that they might have to pay out more than it took in. A new escheat law came into effect in 2004, in which all unclaimed deposits escheat to the state except those on containers that are part of a distributor commingling agreement. (See the Maine Quick Facts page for more information on commingling agreements.)

3. Massachusetts: The first escheat law related to container deposit systems was passed in Massachusetts in January 1989. 8 In the first year of implementation, 10% of the unclaimed deposits went into the state’s Clean Environment Fund (CEF) and 90% went into the general fund. Over the next five years, the percent of unclaimed deposits accruing to the CEF increased, while the percentage going into the general fund decreased. By 1995, 100% of escheated unclaimed deposits were earmarked for the CEF.

The intent of Massachusetts’ original law was to use the CEF exclusively for solid waste management, with specific proportions earmarked to provide support for recycling, composting, solid waste source reduction, and other environmental programs related to the bottle bill. 9 However, the actual allocation of the funds has been subject to appropriation by each subsequent legislature. Instead of receiving up to $226 million available from the CEF from FY 1990 to FY 2002, no more than $60 million (27%) was used to stimulate and support recycling, the bottle bill, and other innovative solid waste programs. 10 The other $166 million (73%) went toward Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) overhead costs unrelated to the original mandate of the law. 11

4. Michigan: Michigan’s escheat law was passed in 1989. 12 The law requires 75 percent of the unclaimed deposits to be transferred into the Cleanup and Redevelopment Trust Fund, overseen by the Michigan Department of Treasury, while the remaining 25 percent is to be distributed by the Treasury to retailers as a way to offset their handling costs.

Amended in 1996, the law specifies how the state must distribute its share of the unclaimed deposits. Eighty percent of this Cleanup and Redevelopment Trust Fund is immediately available for appropriation for municipal landfill cost-share grants, matching federal Superfund dollars, response activities addressing public health and environmental problems, redevelopment facilitation, or emergency response actions. Ten percent is deposited into the Community Pollution Prevention Fund, and the remaining 10 percent is deposited into and must remain in the Cleanup and Redevelopment Trust Fund until the amount accrues to a maximum of $200 million.

5. New York: In 2008, New York passed a law to escheat 80% of unclaimed deposits. In 2013, New York passed a law which requires $23 million in unclaimed deposits to go the state Environmental Protection Fund (EPF), with the remaining unredeemed deposits going to the state General Fund. Escheated unclaimed deposits in excess of $122.2 million are also designated to the EPF.13

6. Vermont: Unclaimed deposits in Vermont are used to fund the Clean Water Fund, which is used to help municipalities, farmers and others implement actions that will reduce pollution washing into Vermont’s rivers, streams, lakes, ponds and wetlands.

The Debate on Who Should Keep Unclaimed Deposits

Beer distributors and soft drink bottlers argue that any unredeemed deposits should be utilized to help them offset their costs of managing the container deposit return system. Others argue that the beverage industry is already keeping revenue from the sale of scrap container materials (aluminum, plastic and glass) as well as the “float” (deposits collected from retailers that can be invested for short-term returns), and that unclaimed deposits are tax-free, windfall profits for the bottler/distributor. They argue that unclaimed deposits, like other types of abandoned property, should belong to the state and be used for public benefit. Nearly every deposit state has attempted to escheat the unclaimed deposits as a source of revenue, usually to fund environmental programs.

The economics of each state's program are unique, and depend upon several factors, such as the mix of material types (e.g., aluminum, plastic and glass), the collection mechanism, access to markets for recyclables, and the legislated handling fee. Some distributors are likely making a net profit because the revenue from unredeemed deposits and sale of scrap add up to more than the handling fees paid out and transportation costs.

However, as the mix of materials shifts away from aluminum and toward plastics, programs become more costly.

What are the redemption rates in the deposit states?

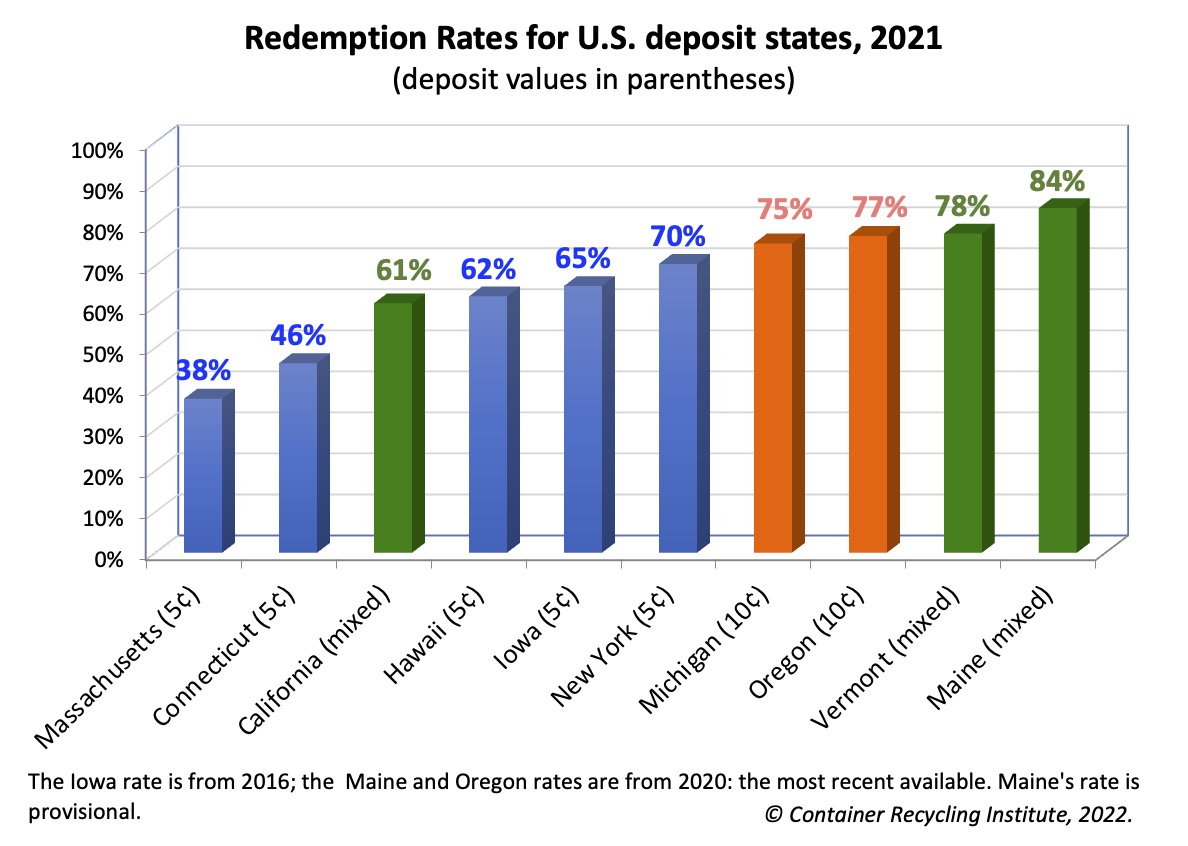

Redemption rates among the 10 deposit states vary widely depending on a variety of factors. The two most important factors are the amount of the deposit ("deposit value"), and consumers' access to redemption options. Higher deposit values and good consumer access to redemption opportunities result in higher return rates and fewer unclaimed deposits.

In states with nickel deposits, the return rates range from 38% in Massachusetts (2021) to 70% in New York (2021). Michigan and Oregon use a 10¢ deposit for all containers and had redemption rates of 75% (Michigan, 2021) and 77% (Oregon, 2020), as the chart below shows.

Three states have mixed deposit values:

- California: the California Redemption Value (CRV) is 5¢ for containers <24 oz., and 10¢ for ≥ 24 oz. (weighted average is 5.4¢).

- Maine: 15¢ deposit for wine & liquor, otherwise 5¢ (weighted average is 5.6¢).

- Vermont: 15¢ deposit for liquor, otherwise 5¢ (weighted average is 5.1¢).

Despite their average deposit values being very similar, Maine and Vermont achieve higher redemption rates than California because they have provided consumers with more redemption opportunities.

Since all the deposit states also have municipal recycling programs, some of the unredeemed containers are recycled either through curbside programs or drop-off sites.

Escheats upheld in court

From 1991 to 1994, the principle of escheating unclaimed deposits survived beverage distributors' legal challenges in three states:

- Maine: In 1991, the beverage industry took the state of Maine to court over the escheat amendment. The law was upheld by a Superior Court, but the Maine Beer and Wine Wholesalers and the Maine Soft Drink Association appealed the ruling. In 1993, the State Supreme Court ruled in favor of the state. 4 The state voluntarily repealed the escheat law in 1995.

- Massachusetts: Suffolk County, MA Superior Court Judge William Bartlett ruled in October 1991 that the Commonwealth's escheat law:

- Did not cause an unconstitutional taking of beverage bottlers’ money;

- Was a proper act of the legislature; and

- That refunds belong to the consumer until escheated to the Commonwealth. The Massachusetts Wholesalers of Malt Beverages appealed this ruling,

However, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ultimately upheld the law in 1993. 5

- Michigan: In 1991, a lower court ruled that unclaimed deposits were the property of the beverage industry and that the law resulted in an unconstitutional taking by the state. The Department of Treasury appealed the case, and the Michigan United Conservation Clubs (MUCC)--the group that had spearheaded the original escheat campaign--put together an amicus brief for the court. They were joined by several other organizations, including the Container Recycling Institute. In 1994 the Court of Appeals overturned the lower court ruling, claiming that the amendment “constituted a valid exercise of legislative powers.” 6 The State Supreme Court chose not to hear an appeal, effectively affirming the Court of Appeals’ ruling.

Endnotes

1. The states are Oregon, Vermont, New York, Michigan, Connecticut, Iowa, Massachusetts, Maine, California and Hawaii. Guam passed a deposit law in 2011,but it has not yet been implemented.

2. Two states require deposits on carbonated beverages and beer only (Michigan and Massachusetts). Eight states (Maine, Connecticut, California, Iowa, Oregon, New York, Vermont, and Hawaii) require deposits on one or more other types of beverages in addition to beer and soft drinks.

4. Maine Beer & Wine Wholesalers Assín v. State (1993) Me., 619 A.2d 94.

5. Mass Wholesalers of Malt Beverages, Inc. v. Commonwealth (1993) 609 N.E. 2d 67, 414 Mass. 411.

6. Michigan Soft Drink Association v. Department of Treasury (1995) 206 Mich App 392; 522 NW2d 643 lv den 448 Mich 898; 533 NW2d 313.

7. Maine escheat legislation is reprinted at the end of this document.

8. Massachusetts escheat legislation can be found below and at http://www.state.ma.us/legis/laws/mgl/94-323B.htm.

9. See St. 1989, c. 653, s. 70 as codified in G. L. c. 94, s. 323F.

10. E-mail with Tom Collins, Director, Division of Local Mandates, MA State Auditor’s Office, Jan. 22, 2003.

11. Ibid.

12. Michigan escheat legislation can be found below and at www.deq.state.mi.us/documents/deq-wmd-swp-Bottle-Bill.doc.

11. Ibid. Environmental Conservation (ENV) CHAPTER 43-B, ARTICLE 27, TITLE 10, § 27-1012. Deposit and disposition of refund values; registration; reports.

Other sources used: “Deposit Initiator Deposit and Payment Statistics, 2008-2017,” prepared by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation; March 15, 2017 email from Sean Sylver, Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, and “Bottle Deposit Information,” prepared by the Michigan Department of Treasury, Office of Revenue and Tax Analysis.

Last Updated on February 1 2023.

Can I take my bottles and cans to a state with a bottle bill and get the refund there?

The very short answer is 'no'. The long answer is, in order to earn a refund, you must have paid a deposit first. The deposit-refund system is based on the idea that a bottle is bought in the state, the deposit is paid, and then the deposit is returned to the purchaser when the container is returned. Containers bought in another state cannot be returned for a refund because no deposit was originally paid in the state giving the refund. It is illegal to try to collect a refund on a bottle or can purchased in another state.

What should I do if I think a grocery store is not following the law regarding the redemption process?

Each state's law are a little different with regards to how and if stores must accept bottle returns. If you have a question, you should check with the organization that administers the deposit system in your state. Visit the legislation page to find contact information for the authorities in your particular location.

Why not put deposits on other recyclable containers? Why focus on beverages only?

There are a number of reasons why deposit laws are enacted specifically for beverage containers, including the nature of the product and its consumption patterns. Beverage containers make up the largest portion (over 80%) of all containers sold in the U.S. Unlike many containers for food and other products, beverage containers are more likely to be emptied away from home (at least 1/3 of all beverages sold, according to calculations by the American Beverage Association). These “on the go” containers are not captured by curbside collection programs, so the financial incentive of the deposit helps encourage consumers to return them to retailers for their refund. Unlike containers such as shampoo bottles and peanut butter and pickle jars, the contents are consumed in minutes, making the container particularly wasteful. They also comprise a large portion (40-60%) of litter, which can be reduced with a financial incentive to recycle.

I disapprove of bottle bills.

You're right, that's not a question! But it is an opinion that people occasionally express, for various reasons. Most of the time, these reasons are misinformed. Visit the page on Bottle Bill Myths and Facts to read rebuttals to the most common arguments against bottle bills.

Advocates of deposit systems have historically pointed to the environmental benefits of bottle bills including litter reduction and energy and resource conservation. In recent years they have also emphasized the waste diversion and job creation benefits of bottle bills. They further argue that bottle bills shift the costs of litter cleanup, recycling, and waste disposal from government and taxpayers to producers and consumers of beverage containers.

Click Any Tile Below to Learn More

- Default

- Title

- Random

-

People without access to curbside recycling still have access to the benefits of bottle bills...Read More

-

Containers collected through bottle bills are cleaner, less often broken, and more liikely to be made into new containers...Read More

-

Bottle bills are an effective means to ensure that the environmental impacts of beverage containers are minimized...Read More

-

The collection of a refund is a powerful motivation for returning beverage containers to be recycled...Read More

-

Bottle bills shift the responsibility for cleaning up waste to beverage producers and consumers.Read More

-

Legislators, media outlets, and the general public, have all expressed overwhelming support of bottle bills...Read More

-

Many tasks associated with the collection and processing of recyclable containers have created jobs in the recycling and retail industries...Read More

-

Every bottle bill recorded has increased recycling rates of beverage containers, which means decreased waste...Read More

-

Beverage containers make up a large proportion of litter, and bottle bills are very effective at reducing that litter...Read More

-

Studies show that deposit systems in conjunction with municipal recycling programs make for very efficient recycling systems...Read More

Although support for deposit laws is widespread, some groups, like members of the beverage production and retail industries, consistently try to prevent bottle bills from being passed or expanded, as well as attempt to repeal existing deposit laws.

In addition to spending huge sums of money to defeat container deposit legislation, these opponents have also tried to sway public opinion in their favor. Their arguments concentrate on the increased costs to bottlers, distributors and retailers, which they claim result in higher prices to consumers. They also contend that bottle bills reduce sales and eliminate jobs in the container manufacturing industry. More recently, they have argued that municipal recycling programs are a more comprehensive means of reducing solid waste and that bottle bills ‘rob’ curbside recycling programs of the valuable aluminum beverage cans, thereby reducing program revenues.

These arguments are not true! The following is a list of common arguments made by bottle bill opponents, followed by facts that support the case for bottle bills.

|

Myth |

Fact |

|

Deposit systems target only a small part of the waste stream. |

While beverage containers constitute less than 6% of the waste stream by weight [1], the upstream environmental effects of container wasting are disproportionately high compared to other recyclables.. For example, beverage containers account for 20% of the greenhouse gas emissions resulting from landfilling a ton of MSW and replacing the wasted products with new products made from virgin materials. [2] |

|

Deposit systems address only a small portion of litter. |

Beverage containers comprise 40-60% of litter in non-deposit states. The Solid Waste Coordinators of Kentucky found that 58% of litter collected consisted of beverage containers, pull tabs, and closures.[3] A 2020 Pennsylvania Litter Study found that plastic beverage containers represent over a quarter (25.8%) of all large litter. [4] Deposit laws significantly reduce container litter AND other types of litter. In 2019, beverage containers comprised 22% of all litter in Virginia, in contrast to only 8.69% on average in deposit states. [5] |

| Deposits aren’t needed where there is curbside recycling. | Curbside recycling and deposit systems are not mutually exclusive. Together they can be part of a comprehensive approach to recycling. Not only are combined curbside and deposit systems more effective than curbside recycling programs alone, the materials collected through deposit programs are of a much higher quality than materials collected through curbside recycling programs. CalRecycle reported that materials collected through single-stream resulted in poorer scrap quality, making it more difficult to recycle than deposit-stream materials. [6] |

| Deposit return is inconvenient (consumers prefer home curbside bins). | Curbside is still not available to 27% of the American population. [7] Curbsides don’t address away-from-home consumption. More and more stores also accept beverage containers in the store, or redemption centers open up close by, making special trips rare. |

| Deposits rob curbside programs of valuable aluminum can revenue. | As it is, curbside programs are failing to adequately capture aluminum cans. Curbside programs do not target cans consumed away from home. Aluminum cans are gradually being supplanted by plastic bottles. [8] Deposits reduce collection costs by removing cumbersome, low-value glass and plastic bottles from the stream. It is also illogical to expect curbside recycling to generate revenue when this expectation has never been made of landfilling or incineration. |

| Deposits are more expensive than other recycling programs. | While their initial costs may be more, deposits are much more effective than other recycling and waste reduction programs, resulting in greater cost-efficiency. The BEAR report found that a combination of recycling methods in 10 deposits states recycles 490 containers per capita per year, at a cost of 1.53¢/unit, vs. 191 containers per capita per year at 1.25¢/unit in 40 non-deposit states. Beverage container recovery rates in deposit states are more than 2.5 times higher than in states without bottle bills. [9] As well, under deposit systems, the cost of recycling is borne by producers and consumers, not by government and taxpayers. |

| Deposit returns are expensive for distributors. | Disposal, curbside recycling, and bottle deposits all have some associated cost; the main difference lies is if the cost will be held by government or by brand-owners, distributors, and beverage consumers. Distributors have taken back-hauling out of the distribution system; they have the ability to design it back in. Distributors have the option of passing the cost of handling on to consumers. |

| “Deposits are a tax” and increase the price of beverages. | Bottle bill opponents call bottle bills "a tax". However, bottle deposits are refundable, meaning the consumer receives their money back. Non-depost beverage containers, meanwhile, are a corporate subsidy, or a hidden tax. Many taxpayers also absorb the costs of recycling beverage containers through curbside recycling programs. When there is a refundable deposit on beverage containers, the consumers (not taxpayers) pay the deposit. The deposit is refunded if the container is returned. Beverage distributors and bottlers absorb the cost of collection. They then choose whether or not to pass their costs on to their consumers. Because 70% or more of the deposit containers are returned, taxpayers pay less for disposal, less for litter pickup, and less for curbside recycling. |

Sources

[1] "Municpal Solid Waste in the United States: 2011 Facts and Figures." United States Environmental Protection Agency. 2013.

[2] “Energy to Waste: Measuring diversion by weight distracts us from more environmentally revelant criteria." Valiante, Usman. Solid Waste & Recycling. April/May 2000. [Print Media.]

[3] "Litter in Kentucky: A View from the Field." Solid Waste Coordinators of Kentucky. May 1999.

[4] "Pennsylvania Litter Research Study." Burns & McDonnell. January 2020.

[5] "Littered Bottles and Cans: Higher in Virginia Than in States with Bottle Bills." Register, Kathleen. Clean Virginia Waterways of Longwood University. 2020.

[6] "An Analysis of the Beverage Container Recycling Program." California Legislative Analyst's Office. 29 April 2015.

[7] "SPC: 94% of US residents have access to recycling, but not all curbside." Rosengren, Cole. Waste Dive. 17 January 2017.

[8] "Beverage Packaging in the U.S., 2000 Edition." Beverage Marketing Corporation. October 2000.

[9] "Understanding Beverage Container Recovery: A Value Chain Assessment Prepared for the Multi-Stakeholder Recovery Project, Stage 1." Businesses and Environmentalists Allied for Recycling (BEAR). 16 January 2002.

Last Updated on 6 May 2021.

All about bottle bills

No time to read this whole website? View the PowerPoint presentation instead. Container Deposit Legislation: Past, Present, Future provides a quick look at the most important facts about bottle bills. This presentation is also a great tool for activists needing to present information in support of a bottle bill.

Definition

The term “bottle bill” is actually another way of saying “container deposit law.” A container deposit law requires a minimum refundable deposit on beer, soft drink and other beverage containers in order to ensure a high rate of recycling or reuse.

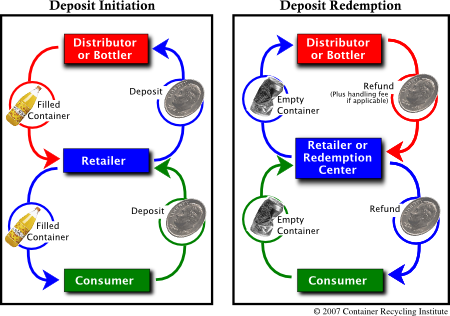

How a bottle bill works

Deposits on beverage containers are not a new idea. The deposit-refund system was created by the beverage industry as a means of guaranteeing the return of their glass bottles to be washed, refilled and resold.

When a retailer buys beverages from a distributor, a deposit is paid to the distributor for each can or bottle purchased. The consumer pays the deposit to the retailer when buying the beverage. When the consumer returns the empty beverage container to the retail store, to a redemption center, or to a reverse vending machine, the deposit is refunded. The retailer recoups the deposit from the distributor, plus an additional handling fee in most U.S. states. The handling fee, which generally ranges from 1-3 cents, helps cover the cost of handling the containers.

The costs to distributors and bottlers can be offset by the sale of scrap cans and bottles and by short-term investments made on the deposits that are collected from retailers. In addition to this income, distributors and bottlers realize windfall profits on beverage containers that consumers fail to return for the refund.

These "unclaimed" or "unredeemed" deposits remain the property of the distributors and bottlers in most states, and amount to millions of dollars a year. In Michigan and Massachusetts, the courts have ruled that because these unclaimed deposits are "abandoned" by the public, they rightfully belong to the state, and they are now used to fund environmental programs in those states. In Hawaii and California as well, the state collects all of the unredeemed deposits, which are then used to administer the deposit system. Learn more about unclaimed deposits here.

Why bottle bills?

In short, bottle bills create a privately-funded collection infrastructure for beverage containers and make producers and consumers (rather than taxpayers) responsible for their packaging waste. There are many other reasons to institute a bottle bill, which are described in the section "Benefits of Bottle Bills."

Why beverage containers?

With so many recyclable materials out there, people wonder why it's worthwhile to focus on beverage containers only. One reason is that beverages compose 40-60% of litter. A deposit encourages people to return these containers, keeping them off the streets and out of the waterways and wilderness. According to industry estimates, one-third of beverages are consumed on the go—away from the home recycling bin and often in places where recycling is not available. The refundable deposit helps ensure that these containers are saved and recycled. In addition, recycling beverage containers rather than manufacturing new ones prevents the consumption of enormous amounts of energy and the emission of great quantities of greenhouse gas emissions.

History of bottle bills

For decades we drank our beer and soda from refillable glass bottles that were reused dozens of times before being discarded. Then, in the 1930’s, the steel beverage can was introduced on the market, revolutionizing the beverage market. Unbelievably, consumers were encouraged to toss their empty beer cans out wherever they happened to be.

For decades we drank our beer and soda from refillable glass bottles that were reused dozens of times before being discarded. Then, in the 1930’s, the steel beverage can was introduced on the market, revolutionizing the beverage market. Unbelievably, consumers were encouraged to toss their empty beer cans out wherever they happened to be.

It was not until after World War II that cans began replacing glass bottles in the beer industry. The convenience and disposability of cans helped boost sales at the expense of refillable glass bottles, and by 1960 approximately 47 percent of beer sold in the U.S. was packaged in cans and no-return bottles. Soft drinks, however, were still sold almost exclusively in refillable glass bottles requiring a deposit. Can market share was just 5 percent. With the centralization of the beverage industry, and a more mobile and convenience-oriented society, the decade of the sixties witnessed a dramatic shift from refillable soft drink ‘deposit’ bottles to ‘no-deposit, no-return, one-way’ bottles and cans.

The gradual demise of refillable beer and soft drink bottles in the fifties and sixties and the rise in one-way, no-deposit cans and bottles resulted in an explosion of beverage container litter. This prompted environmentalists to propose bottle bills in their state legislatures that would place a mandatory refundable deposit on beer and soft drink containers.

The first bottle bill was passed in Vermont in 1953. However, it did not institute a deposit system. It merely banned the sale of beer in non-refillable bottles. The law subsequently expired four years later after strong lobbying from the beer industry.

By 1970, cans and one-way bottles had increased to 60 percent of beer market share, and one-way containers had grown from just 5 percent in 1960 to 47 percent of the soft drink market. British Columbia enacted the first beverage container recovery system in North America in 1970.

In 1971, Oregon passed the first bottle bill (also known as a deposit law) in the United States, requiring refundable deposits on all beer and soft drinkcontainers. By 1986, ten states (over one-quarter of the U.S. population) had enacted some form of beverage container deposit law or bottle bill.

The so-called 'bottle bills" were intended not only to reduce beverage container litter, but to conserve natural resources through recycling and reduce the amount of solid waste going to landfills. They proved to be extremely successful in achieving those goals.

Seven states reported a reduction of beverage container litter ranging from 70 to 83 percent, and a reduction in total litter ranging from 30 to 47 percent after implementation of the bottle bill. High recycling rates were also achieved.

Today, ten states and every Canadian province have a deposit law requiring refundable deposits on certain beverage containers. Although bottle bills meet with opposition from many members of the beverage and grocery industry, several states and provinces have expanded their laws to cover beverages such as juice and sports drinks, teas and bottled water—beverages that did not exist when most bottle bills were passed.